/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/71244833/usa_today_18798647.0.jpg)

Even before a ball had been kicked, D.C. United supporters could observe differences between the Wayne Rooney era and the previous regime.

The day after Rooney was unveiled as head coach, D.C., hosting the Columbus Crew, set out in a back four, having exclusively played with a three-man backline for 18 months prior.

Against the Crew, D.C. lined up in a nominal 4-4-2, though Rooney has since switched to a 4-3-3.

Irrespective of the defensive shape, however, the ideas in possession have remained the same over Rooney’s time in charge:

1) The goalkeeper acts as a sweeper keeper. When D.C. United has the ball, he moves into the space behind his backline, effectively serving as an eleventh outfield player. This allows the No. 6 to remain on the second line rather than having to drop between the center backs to aid in the build up.

2) A traditional No. 6 is used. He sits centrally in front of the backline, rarely dropping deep or venturing wide. His positioning is key to Rooney’s style of play, which centers on building out of the back. Since the Englishman was hired, most of D.C. United’s opponents have defended out of a 4-4-2. It’s easy for two forwards to press a defensive line of three that’s set up as a 1-2 (i.e. when one player is deeper), as is created when a No. 6 drops between two center backs. When one of the “2” (a center back) has the ball, one forward applies pressure while the other covers the middle. This eliminates the far-side center back from the play, turning a 3-v-2 into a 2-v-2. Using a traditional No. 6 mitigates this issue by creating a 2-1 as opposed to a 1-2. As a result, forwards must be wary of the space behind them, making it more difficult to press.

3) The fullbacks push up and the wingers tuck inside. By staying wide, the fullbacks stretch the field horizontally, opening up gaps in the opponent’s backline. These can be exploited by the wingers, who come inside to create overloads in the middle.

4) The wider central midfielders rotate into the positions in which the fullbacks started. This is the wrinkle that sets D.C. United apart. Most teams that build out of the back ask their No. 8s to push forward (practically in line with the striker) and serve as playmakers in order to create overloads in front of goal and set up a rest defense.

The difference between those teams and D.C. United lies in where they generate possession. Whereas, say, LAFC dictates its games from the opponent’s half, Rooney wants his team to move the ball around its defensive third in order to pull the opponent upfield. When the central midfielders rotate wide, the center backs split to the corners of the 18-yard box, creating passing angles. As the opponent steps forward in an attempt to win possession, D.C.’s center backs collapse toward the middle to form a narrow triangle with the goalkeeper.

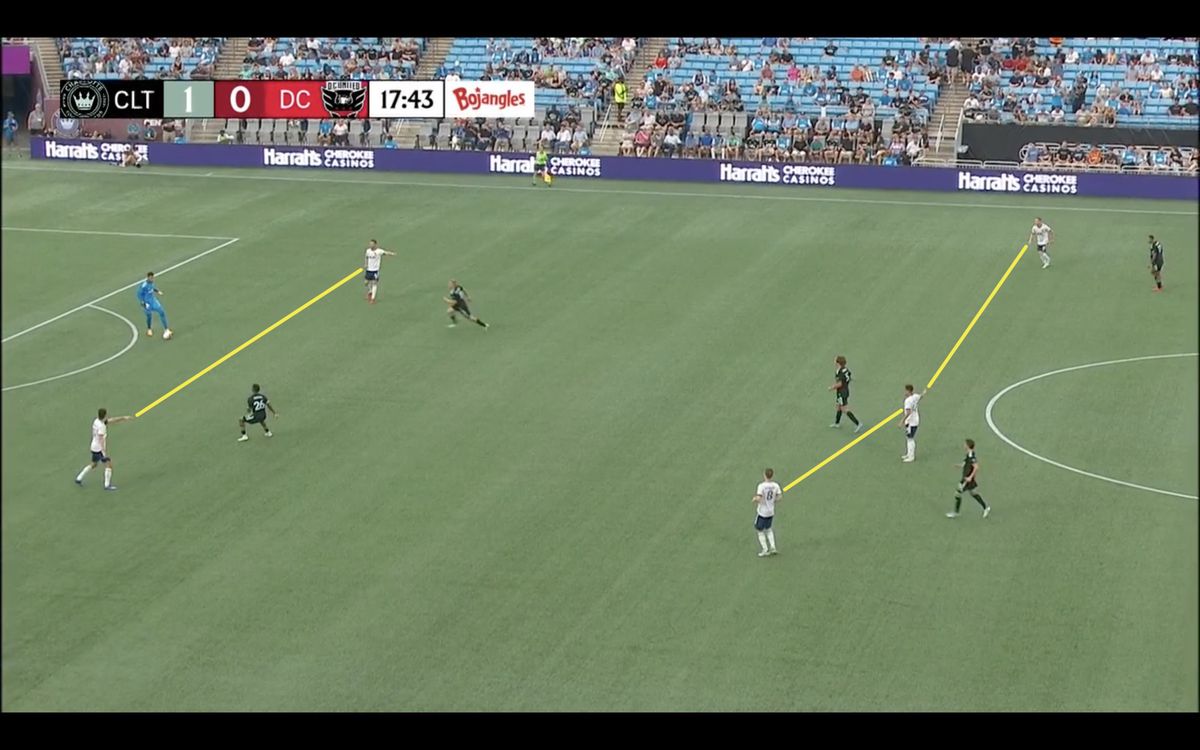

That triangle is essentially a line of three arranged as a 1-2, which, as discussed, is easy to press. If that seems counterintuitive, remember that D.C. is trying to lure the opponent forward. Once it has done so, D.C.’s central midfielders slide into the half-spaces, creating a 2-3-5 shape in possession:

That image is from the 18th minute of D.C. United’s loss to Charlotte FC in what was Rooney’s second match on the sidelines. Rewind 50 seconds and D.C. is defending out of its 4-3-3, with Russell Canouse (left) and Chris Durkin (right) on either side of Ravel Morrison in midfield.

Charlotte’s left center back, Anton Walkes, overhits a long ball, which Rafael Romo comes off his line to collect. D.C. proceeds to knock the ball around its defensive third for almost 40 seconds, during which Steven Birnbaum and Brendan Hines-Ike move toward the middle as described. At one point, Hines-Ike shapes up to pass the ball to Canouse (who has rotated to the left flank) but, noticing that Yordy Reyna is about to take the bait, squares it to Birnbaum instead. Charlotte’s left winger bites, breaking his team’s defensive shape when he closes Birnbaum down. That’s the queue for Durkin to come inside from the flank. This movement, while subtle, is important because it gives Romo the option for a through-ball.

That forces Charlotte’s left-sided No. 6, Brandt Bronico, to make a decision on whether to step to Durkin, eliminating that passing option, or remain in front of his backline to deal with D.C.’s line of “5”.

Ultimately, Bronico decides to step. Had he not, Romo could have found Durkin in the pocket, as he repeatedly did in D.C.’s loss to CF Montréal in July. In that match, Durkin started most of his team’s attacks, receiving the ball in the left half-space and driving it forward or playing Jackson Hopkins in behind.

Returning to the play against Charlotte, once Bronico steps, Chris Odoi-Atsem, having pushed up from right back, is isolated one-on-one with Charlotte’s left back (and former D.C. United defender), Joseph Mora.

Romo plays a lofted ball to Odoi-Atsem, forcing Mora to step off his backline and challenge in the air. As a result, Hopkins finds himself with yards of space in the center of the box seconds later:

There’s that line of “5” that has been alluded to.

Once Durkin lays the ball off to Sami Guediri, D.C. United has three options in the center of the box, a player at the back post and a runner from midfield. This overload is difficult to contain, especially for teams that defend with a back four. Fortunately for D.C., the three-man backline has fallen out of favor in MLS this year. The Black-and-Red are proof, having exclusively played with a back three in 2021.

Ultimately, this is the goal. The rotations and use of the ball in the defensive third are designed to isolate the line of “5” against the opponent’s backline. These five players can each occupy one of the vertical zones, stretching the field horizontally in order to open gaps in the opponent’s backline that the overload of attackers in the middle can exploit.

While that sounds great, flaws exist. For one, none of the fullbacks seem to fit Rooney’s system apart from Andy Najar and Kimarni Smith. Injuries, however, have limited the former to 12 starts this year – nine in which he was substituted. The latter, meanwhile, is in the midst of a transition from winger to left back and has less than 350 minutes across two seasons in MLS.

Other concerns have arisen as well, leading to some words of caution:

1) D.C. United must be aggressive with its passing. There’s an element of risk to building out of the back, so players must be brave on the ball, willing to break lines and receive passes in difficult situations. Rooney lamented his team’s inability to do so following its loss in Charlotte:

Rooney says #DCU moving to 433 for the night was about having the wide forwards funnel Charlotte into the middle, & then have 3 players in that area to be hard to play through from there. Says the lack of being aggressive with the ball undid the attacking side of that plan.

— Jason Anderson (@JasonDCsoccer) August 4, 2025

2) Players on the line of “5” must check into midfield. With the numbers that D.C. United commits to the attack, the opponent’s defenders cannot risk following a forward into midfield. Doing so would open space for D.C. to play in behind. Thus, when one of the “5” drops in, he can receive passes between the lines with space to turn and progress the ball. This is crucial once the central midfielders have rotated wide, as D.C. only has one option in the center of midfield during that portion of the build up.

Taxiarchis Fountas tries to drop in but he’s a liability on the ball in those positions. For as much as he offers in the attacking third, he lacks that Luciano Acosta-esque ability to take the ball off his midfielders, turn and eliminate players on the dribble, nor is he able to unlock a defense with one pass. He tries too much on the ball when deep, leading to the types of turnovers that have killed his team.

Hopkins has dropped in most effectively. Against Orlando City, D.C. United’s best look prior to stoppage time (accounting for 0.32 of its 0.63 xG in regular time) originated with him dropping off the frontline. That forced Durkin to find space higher up the field, from where he was able to pick out Fountas with a cross.

D.C.’s game-winner against the Lions came from Martín Rodríguez dropping in and hitting a long diagonal to Smith, who served Fountas on a platter:

TAXI!

— Major League Soccer (@MLS) July 31, 2025

Fountas finds the go-ahead goal for @dcunited! pic.twitter.com/F4Cs2uNcNC

3) Once the opponent’s forwards step, D.C. United’s midfielders must rotate back inside. In Minnesota, for example, D.C.’s shape in the build up looked more like a 4-1-5 than a 2-3-5; Drew Skundrich hugged the sideline, and neither he nor Durkin toggled between the first and second lines in possession. This left Sofiane Djeffal as the team’s only option in midfield when building out of the back. Due to a lack of numbers on the second line, D.C. struggled to play through the Loons’ first line of pressure. Too often, the team would resort to kicking it long, turning purposeful possession into 50-50s.

That match in Minnesota occurred four days after Rooney was unveiled as coach. While it hasn’t been perfect, the team is improving its understanding of the Englishman’s ideas and implementing them at a higher level with each passing game.

Time will tell how high a level D.C. United is able to reach.

Loading comments...